The Fed, collateral and repo: more systemic risk?

Friday, July 19, 2013 at 01:22PM

Friday, July 19, 2013 at 01:22PM

We’ve had the FT article of April 23, 2013, The Misuse of Collateral Can Help Create Systemic Risk by Satyajit Das, on our desk for several months. It is highlighted and underlined, and we borrow from it liberally here (in fair use we trust). His article was prescient.

The thesis is simple enough: in the main collateral is now the basis of our primary financial institutions, most capital markets transactions, and source of liquidity, which is to say, our entire financial system. One might infer that collateral is what you use when you have no capital. He highlights, excerpted below, some consequences, intended or not, of the increasing dependency on collateral. Translation: “you can run, but you can’t hide.”

First, it shifts the emphasis from the borrower or counterparty’s creditworthiness to the collateral. Parties normally ineligible to borrow or transact in the first place are able to enter into transactions. Rapid growth in debt levels, derivative contract volumes and the shadow banking system (hedge funds or structured investment vehicles) are dependent on the use and availability of collateral.

Second, the security offered as collateral is not risk free, even if it is government bonds. This introduces exposure to unexpected changes in the value of the collateral. Wrong way correlation, where the underlying risk increases at the same time as the value of the collateral decreases, reduces its utility.

Third, it assumes liquid markets for the collateral, which must be realised in case of default.

Fourth, asset liability mismatches compound the risk. For example, where the loan is for a shorter maturity than the security pledged, or where collateral must be adjusted frequently over the life of the transaction.

Fifth, collateral in practice introduces significant operational and legal risk, including enforceability of security.

Sixth, the use of collateral introduces moral hazard. While lowering collateral levels decreases protection, pressure to increase business volumes may lead to inadequate collateralisation, increasing leverage.

Finally, collateral has systemic effects, altering the functioning of financial markets, especially the quantum of credit available, liquidity risk and behaviour.

This takes us to the repo market, the heart of how dealers finance inventory, including but not limited to, the entire US Treasury market globally, so think $big. A repo is a simple trade but the jargon can be tough. Think of it as a secured loan. Simplistically, a dealer buys a $100 bond and wants to finance it. To finance it the dealer gives you the $100 bond as collateral, and you give him, cash, say $98. The trade is unwound at the end. On a good day the dealer buys his bond back from you at the pre-agreed price, and you get your interest for making the loan. The cost of financing for the dealer is determined by the "repo rate" which is determined by the market, the supply and demand for particular issues. And not all bonds are equally attractive. The fresh stuff, the most recently auctioned Treasuries (known as "On the Run"), is generally in greater demand. Most repo is overnight, some goes to longer terms.

Pretty simple, but one perspective might help. Demand in the market tends to be driven by particular securities. A "special" is an asset that is subject to unusual demand in the repo and cash markets for that asset. So if you need a particular bond, you can buy it directly or obtain it for through the repo market (that is, you get the bond as collateral). This causes buyers for that bond in the repo market to compete for the asset by offering cheap cash in exchange. Sometimes need for specific bonds or the scarcity of specific bonds drives the repo rates to "special".

Mr. Das points out “in periods of stress, market participants all seek more collateral or need to sell pledged securities, increasing market instability.” This calls to mind many of firms formerly known as Bear Stearns, Lehman, Merrill Lynch who experienced the lethality of collateral calls in volatile markets, and the current TBTF crowd including AIG, GE, Goldman, JP Morgan, Citi, and a bunch of others who were bailed out before the bullet hit. So, in the context of under capitlized financial institutions, if you’re out of capital you had better have a pantload of collateral, right?

Now to the recent Fed action: what hypothesis might explain the Fed’s recent actions, the contradictory tapering talk, then "really, we just changed our minds." What to make of it? Why the abrupt change?

The repo market is a big deal. No repo or stress in the repo market impacts liquidity which means really bad things. Special repo means you're paying up to get the bonds, very costly. Rates can and do go negative, which means they don't pay you to finance their inventory, you pay them to get the bond.

When you’re rattled by collateral, do the Fed taper talk from the Financial Times of July 19, is excerpted below and warrants a full reading.

Bernanke is talking as if the goal is to change the mix of monetary policy but not the level of accommodation, essentially trading some reduced accommodation from ending asset purchases for additional accommodation by extending the forward guidance on interest rates. But why? If the level of accommodation is the same, does the mix matter? That’s an interesting question - does the Fed have research saying the mix matters, and why?

I can see two reasons. One is that somehow asset purchases have a more negative distortionary impact. Another is that there exists an internal bias in the FOMC against expanding the balance sheet.

Well, we know about the general distortion of the global securities pricing induced by QE. So do they, so that's not new information. But we don't get inside the kimono, so to speak, in the repo markets, nor do we receive flash reports from the global central banks on global money center bank liquidity. If one infers the bias against expanding the Fed balance sheet is motivated by a dim recognition of an absolute constraint of orderly market operation or worse, evidence of it... and what might be this "distortionary impact"?

The FT article suggests commentary from Alhambra Investment Partners , QE Moved Out of On The Run as a source of insight:

“For some reason, collateral continues to be short of demand in repo markets and the re-openings have not fully satisfied them. What the SOMA [Systems Open Market Account , jargon for the QE portfolio] data above suggests, and highly so, is that the Fed recognizes the role of QE in removing OTR [On The Run] collateral. Why else would they start by purchasing relatively high proportions of OTR’s and then drop to nothing, or nearly nothing, after the repo markets went so special? [emphasis added]. It seems pretty clear to me that the Fed noticed the repo warnings and acted, thus confirming, operationally, what we have suspected about QE.

Since then, the Fed has remained out of the OTR space almost entirely. But that might not fully help either since there is a growing proportion of OFR [Off the Run] in the SOMA portfolio. While the Fed can and does “rent” out SOMA collateral, it adds another layer of cost and complexity to repo markets that for some reason don’t want to follow the “normalcy” script. Therefore, it’s not a perfect solution to the shortage. Bottom line is I believe collateralized lending markets, the marginal source of effective liquidity post-2007, are short of collateral for numerous reasons, leading to all manner of side-effects. I think this data confirms that the Federal Reserve agrees, including the role QE may be playing.

We don’t know the firm, but their tactical analysis is spot on. Perhaps the Fed has inadvertently transplanted the liquidity problem from banks to the repo markets? Do we have under capitalized institutions now experiencing collateral shortages? Was there an aroma of a potential liquidity problem or the prospect of a specific event? A near miss? We don’t know. Was there market stress? It would seem. Would the Fed tell us? Again, we think not, particularly if disclosure might compromise the theological hopium of QE.

Oh, we forgot to tell you about re-hypothecation. It's fun! Let's go back to the repo. Dealer buys a bond, repos it. You now have the bond as collateral. You've got the scarce item. What do you now do with your precious collateral? You re-hypothicate it, which is to say you repo it out to another party. Repeat, rinse and wash and distribute to a global matrix of financial institutions. Add price volatility, add collateral scarcity. And who takes your collateral? It goes to the point of greatest demand, which in a dark scenario may be the weakest hand with the desperate bid.

Given the size of the global repo markets (more $ zero's than you can imagine) may we safely assume that the proper risk management controls are in place? After all, the Fed & the regulators have had since 1999's Long Term Capital to understand & sort out the nasties of global matrices of exposure.

Well, let's see what they say in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Report, Repo and Securities Lending, Revised February 2013:

Let's read this part again, "the existing data sources are incomplete". We take them at their word that they don't know the risk. Perhaps this is viewed merely one more minor administrative detail to be sorted out in due course. We view it as a grossly negligent suffering of structural moral hazard: the global markets know they have a put option to the US taxpayer.

Our outllook on the Fed

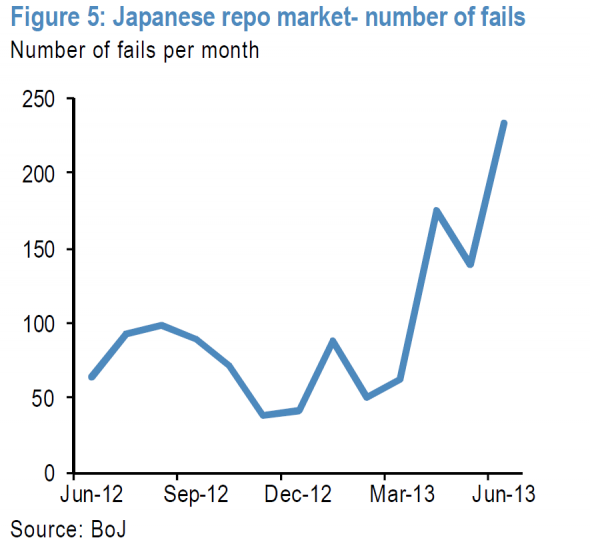

We're still left with the Fed and QE. Our take is that QE has inadvertently induced a shortage of high quality collateral which has manifested itself in the repo markets. Clearly, there has been stress in the repo market. Squeezing one end of the balloon causes it to expand elsewhere, and we suspect, but do not know, that there was either some type of near miss of a liquidity event somewhere, or blinking lights on the dashboard that caused the Fed to seemingly and publicly reverse in short order the whole tapering rap. We don't see this as a strategic shift but rather a tactical mid-course correction executed by Alfred E Newman. Maybe all the tools they thought they had have some constraints.

We believe the Fed is in fact looking for an unwind strategy but can't find one. A financial Burdian's Ass? Does any bale of hay contain an acceptable unwind? We've gotten a whiff of the revolt of the rational market investors squaring off on the 10 year rates at any sign of tapering which was not pretty.

Our take is that the Fed will do nothing intemperate, take an agonizingly slow incremental approach ... at least while all the knots hold. By this we mean near stasis. We suspect the probabilities are growing for a much longer & slower unwind than many contemplate. We are, however, unwilling to bet much of the ranch on it. The stasis scenario provides 'flexibility' for a strategy that is pinned to the hope of economic growth that may or may not materialize. One is tempted to suggest decades and for the intermediate period a near permanent increase in the money supply. Just a thought. Watch money velocity.

Oh, speaking of dusty items in the should-do-something-with-this pile on the desk, did anyone notice the premia for physical gold in Asia vs. paper gold? Could it be consumer preference? Custody risk? Just wondering...

hb

hb

How timely. This just in

When Central Bankers Fail - A Tale Of Two Broken Bond Markets

hb

hb

hb

hb

SEC Warns: Prepare For Repo Defaults on 07/22/2013 21:28 -0400

hb |

hb |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  repo,

repo,  systemic risk,

systemic risk,  uncertainty

uncertainty

Reader Comments